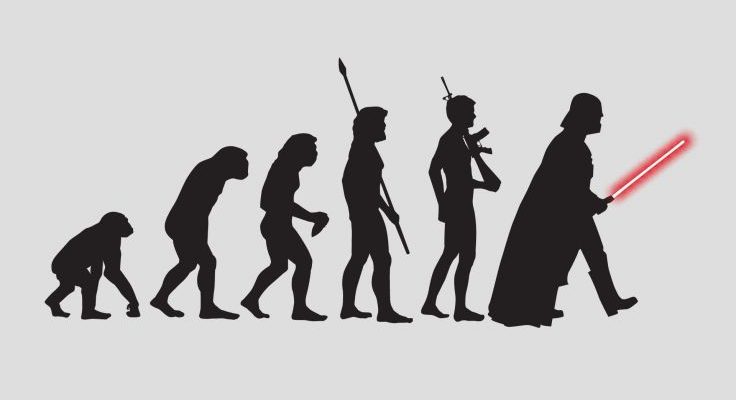

I read Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Harari earlier this year, and thought it one of the most intriguing books I’ve read. The author ambitiously goes through 2 million years of human history, from the first appearance of homo habilis all the way to modern times, all in the course of 400 pages. The book was not written as a treatise with supporting scientific studies for all its theories, but rather a survey over human history that tries to explore the questions “how” and, perhaps more controversially, “what if”? The writing is captivating, meant for the layperson rather than the academic, and sometimes does make you want to fact check a few things. What I loved the most about the book is the way it makes you question things you take for granted, like the superiority of humans above all the other creatures on earth, or the idea of continuous human progress being a good thing. Not that I necessarily agree with him on all this theories, but he does bring a unique perspective, which is often lacking in today’s discourses.

The first major point the author makes is that homo sapiens really aren’t all that special. It’s hard to hear, having been told on our lives that we are the kings and queens of the world, responsible for its maintenance and possibly its destruction. That latter part is true, however, we didn’t used to be very special. It’s not that we were particularly gifted when we first evolved into existence, we were just the children of one genetic mutation that happened to stick. We were not anointed, but by virtue of the cognitive evolution, we hit the jackpot, and as soon as we were able, we managed to start destroying everything else.

The second point that I thought was especially intriguing is the author’s argument that the agricultural revolution wasn’t the best thing that happened to us as historians like to claim. True, the agricultural revolution gave humans the ability to grow their population at an exponential pace, but also made our lives a lot harder. The author makes the provocative argument that perhaps we would have been happier if left alone with our hunting and gathering. I don’t know whether that is true, but I do think that it’s worth thinking about the price we pay in the name of progress. Increased productivity has led to increased consumption, but not necessarily increased happiness or fulfillment. Current political developments have gotten me to think a lot more about inequality, a few recent books/documentaries like Inequality, Evicted, and Hillbilly Elegy have provided some great food for thought. Even when it comes to the idea of globalization, which I have supported as long as I remember, I’m beginning to wonder if it’s really a good thing in today’s climate. The extra benefits globalization brings to consumers, spread over millions of people, amounts to so little for each person, while the tremendous burden it drops on a small group is devastating. It’s not that we can’t both have globalization and help these people, but that requires some form of redistribution of wealth, which our current political system just won’t support. So as we continue to explore new technological improvements that increase productivity, how can we pause to examine whether these advancements are actually also contributing to the overall satisfaction of people?

One idea I really liked was the role myths played in driving societal evolution. Whether it be the myth of a creation theory or the myth of nation states, these things are so powerful in terms of uniting people, as well as diving them, thus forming our current landscape of groups of people fiercely defending their own unsubstantiated abstract concepts, often to the death. Concepts like morality, values, and political order are also simply imagined myths with no objective support. I guess that’s why we fight so often about those too. I can see why it makes sense for some people to just want their choices to be taken away and given a simple “truth” to follow. This is actually an idea greatly explored in Eric Hoffer’s True Believer, where the author’s piercing insights into mass movements from the 1950s carry great weight when applied to today’s society.

Since I already veered away from my initial book, I might as well bring up Guns, Germs, and Steel, which I finally finished after months of leaving it on the shelf. Compared to Sapiens, the book was more dry, focusing on pulling together robust scientific support for the arguments being made. Rather than answering the question “how did human beings end up on top of the food chain,” GGS tackles a smaller, but no less complicated question of “how did the West end up on top of the world?” I think the biggest takeaway I have from the book is that, from the very beginning, people were not created equal. Environmental differences determined whether the native vegetation and animals can be domesticated, which gave certain continents significant advantage over others in terms of the agricultural revolution. This also caused a chain reaction, since, for example, the germs that the Spanish brought to America which practically wiped out the native population were native to the animals they domesticated, and so on.

Digressing even further, and perhaps somewhat on a tangent, the end of Sapiens looks outward into the future, and posits what life would be like, and could be like, given our current course. This reminded me of Seveneves, a sci-fi novel that starts with the assumption — what if the moon blew up? The book ambitiously imagines the world scrambling into action, then resorting to just sending a few people into space to avoid total extinction. From there begins the great epic of the entire human race using their creativity and resilience for survival, while not forgetting to fight for power amongst themselves along the way.

As far as we know, humans are still the only creatures capable of doing exactly what I’m doing now — looking into the past, questioning the present, and imagining the future. This unique gift doesn’t always bring us joy, as we fill ourselves with doubts, fears, and regrets on a daily basis. Still, it’s such a marvel and privilege to be human.

Leave a Reply